ABSTRACT

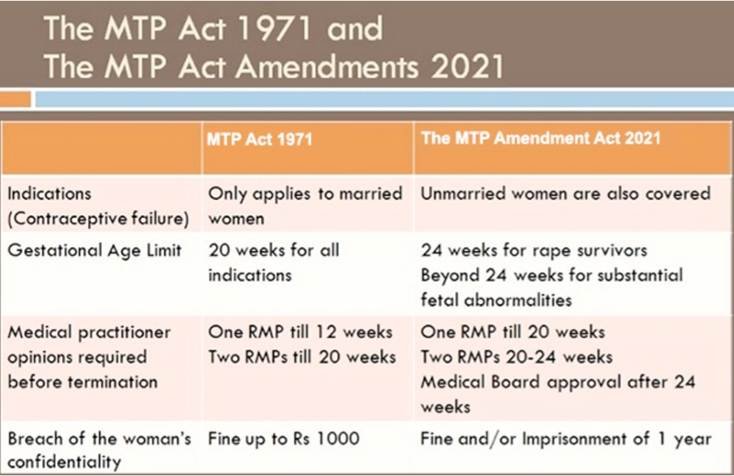

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971, represented a landmark legislative step in India’s approach to reproductive health and women’s rights. Enacted to liberalize abortion laws and reduce maternal mortality arising from unsafe abortions, the Act allowed termination of pregnancy under specific medical, humanitarian, and social grounds. However, as societal attitudes toward women’s autonomy evolved and medical technology advanced, the provisions of the 1971 Act were increasingly viewed as restrictive and outdated. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021, was introduced to address these limitations and align the legal framework with contemporary notions of gender justice, privacy, and reproductive choice.

The 2021 Amendment extended the permissible limit for abortion from 20 to 24 weeks in certain categories, recognized the rights of unmarried women to seek termination on similar grounds as married women, and mandated stricter confidentiality of the woman’s identity. These reforms sought to reflect a more inclusive and compassionate understanding of reproductive health, emphasizing the importance of bodily autonomy and informed consent. Nevertheless, challenges remain—particularly concerning medical access in rural areas, ambiguity around the role of medical boards, and the persistent stigma surrounding abortion.

This research critically analyses the legislative evolution and judicial interpretation of the MTP Act from 1971 to 2021, assessing its impact on women’s health, rights, and social justice. It explores the balance between state regulation and individual freedom, arguing that while the 2021 Amendment marks progress, further reforms are essential to fully realize reproductive rights as a facet of fundamental human rights. The study concludes that effective implementation, public awareness, and gender-sensitive healthcare mechanisms are vital to ensuring that the promise of safe and legal abortion becomes a lived reality for all women in India.

INTRODUCTION

Women have utilized many forms of abortion and contraception throughout history. However, these practices are at the centre of a broader philosophical struggle that challenges fundamental ideas like motherhood, the state, the family, and young women’s sexuality. They go beyond simple scientific and medical considerations. They have so sparked contentious debates on moral, ethical, political, and legal matters. Access to abortion services has often been impeded by legal and societal barriers for women. Women’s ability to exercise their reproductive rights has been restricted by these laws, leading to covert or obvious methods of abortion. Abortion laws have changed throughout time to take into account societal and historical circumstances. These regulations have consistently attempted to satisfy social expectations, usually at the expense of women’s autonomy, despite variations in form, purpose, and approach in matters pertaining to reproduction, fertility, and sexuality. An important step toward recognizing and controlling pregnancy terminations in India was the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of 19711.

However, the current law must be amended due to shifting views on reproductive rights, medical developments, and societal changes. To fill in the gaps and bring the law up to date with the times, the Indian government passed the MTP Amendment Act in 20212. Significant changes were made by the MTP Amendment Act 2021, including raising the gestational limit for abortions, expanding access to safe abortion services, strengthening privacy and confidentiality protections, and incorporating digital platforms for effective data management. The goals of these modifications were to protect women’s health, encourage their reproductive autonomy, and curtail dangerous abortion practices. This study conducts an investigation into Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971: Section 88 of BNS makes it illegal to intentionally cause a “miscarriage” in India.

However, in certain situations, this Act permits a medical expert with specialized training to end a pregnancy. Stated otherwise, Section 312 is an exception to the MTP Act. In India, it governs the process and the conditions that allow for abortion in specific situations. It categorizes situations in which a pregnancy could be ended as follows (after the 2021 amendment). on a single doctor’s recommendation, up to 12 weeks after conception. on the recommendation of two physicians, between 12 and 20 weeks after fertilization. Only in specific instances, between weeks 20 and 24 of pregnancy conception, of pregnancy, only in certain cases, on the advice of Two doctors.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY ACT, 19713

After extensive consultation with specialists, medical professionals, consultants, and other ministries, Dr. Harshvardhan Goyal of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare introduced the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Bill 2020 to the House of People on March 2, 2020. This bill’s primary objective was to modify the current The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 governs abortions that are permitted and lawful. To increase the Act’s efficacy, the proposed Bill also sought to amend certain of its sections. The Bill sought to give women a safer way to end pregnancies they did not wish to continue by expanding the legal window for abortion from 20 to 24 weeks. To protect expectant mothers, it also emphasized enhancing privacy, accounting for gestational age, and implementing safety protocols. Additionally, the proposed law aimed to modernize healthcare and medical practices that the 1971 Act did not cover. Abortions after 20 weeks were prohibited by law, particularly for women who had experienced sexual assault, rape, or physical or mental health issues. The objective Abortions beyond 20 weeks were prohibited by law, particularly for women who had experienced sexual assault, rape, or physical or mental health issues. The goal was to make safe medical methods of pregnancy termination available to all women, even those from underprivileged backgrounds.

OBJECTIVES OF THE MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY ACT, 1971

The Preamble of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 lays out the Act’s purpose. According to the Act’s Preamble, “An Act to provide for specified pregnancies to be terminated by licensed medical professionals and for matters related or incidental thereto.” Only some pregnancies may be terminated by licensed medical experts in accordance with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971. The Act’s main goals are to improve Indian women’s maternal health and lower the number of women who die because of unsafe and unlawful abortions. Women were only granted the right to safe abortions under certain conditions following this legislation.

CONDITIONS FOR TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY UNDER THE MTP ACT ,1971 4

Section 3 of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, states the conditions under which pregnancy can be terminated. According to Section 3 of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, “When pregnancies may be terminated by the registered medical practitioners.”

- A licensed health professional who terminates a pregnancy in accordance with the law should not be held in violation of any crime listed in the Indian Penal Code, 1860, or any other legislation at the time of the medical procedure.

- Where the gestational period has not lasted longer than 12 weeks.

- Where the length and duration of the pregnancy has exceeded 12 weeks but not 20 weeks. The same should be decided on a case-to-case basis by the authentic assessments of the two doctors.

- When there is a probability that the unborn child will have poor physiological and mental health and may also be disabled.

- It is crucial to keep in mind that any girl under the age of 18 who is insane or of unsound mind cannot have her pregnancy terminated without her guardian’s or parent’s written authorization.

- A woman’s bodily or mental health will be in great danger if the pregnancy is allowed to continue.

Hence, these are some of the conditions where medical termination of pregnancy is allowed. However, not all women have the privilege to opt for the termination of pregnancy as a matter of right.

In the United States of America, women have the freedom to opt for medical termination of their pregnancy as a matter of right of reproduction, which is included under the fundamental right – The Right to Privacy. Until recently changed, this used to be the case in the United States of America.

The scenario is not the same in India. In India, all women are not allowed to medically terminate their pregnancies. As per the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, only married women and rape victims are allowed to terminate their pregnancies. Unmarried women, widows, as well as divorced women, are deprived of their right to terminate their pregnancies. So, these women have two options – either to continue their pregnancy or to opt for illegal methods of termination of pregnancy. Even married women do not have a fully qualified right to abort as they are supposed to prove the failure of contraceptives to avail themselves of the facility of medically terminating the pregnancy. This violates the fundamental right to privacy.

There are several other conditions under which the child can be aborted medically. These conditions are:

- As stated under Section 3(2)(b) of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, termination of pregnancy is allowed till the 20th week and not more than that.

- As per Section 3(2)(b)(ii) of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, there is a significant chance that the foetus, if it were to be delivered, would be severely handicapped due to physiological or mental defects. In this case, the pregnancy can be medically terminated.

However, there are several tests that are performed in the 20th week of pregnancy to detect the abnormality of the foetus, and such abnormality is confirmed only after the completion of 20 weeks of the gestation period. This raised several questions about the applicability of the above-mentioned sections of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971.

Other significant provisions of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 include:

- Section 2(d) is another important provision of this Act. This provision provides the definition of a “Registered Medical Practitioner.” As per Section 2(d) –

“A Registered Medical Practitioner means any medical practitioner who possesses the required medical qualifications which are defined under Section 2 of the Indian Medical Council Act of 1956 and whose name has been registered in the state medical register and who possesses the required medical skills in gynaecology and obstetrics which are prescribed under the said act.”

- The destination of the pregnancy termination is specified under Section 4 of the Act. It implies that all public hospitals that are properly furnished with the required resources are allowed to offer abortion services.

- Section 5(1) of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 establishes two key conditions pertaining to abortion, which assert that if the concerned doctor acts in good faith as well as due diligence and determines that it is essential to carry out the termination of pregnancy, it would not be compulsory by law to accept the medical opinions of two registered medical practitioners. Additionally, it states that if it is discovered that the termination was conducted by a non-registered healthcare professional, it would constitute a criminal offence.

LIMITATIONS OF THE MTP ACT, 1971

- The Act does not include a qualified right to abort a pregnancy after 20 weeks. It also includes various legal challenges. As a result, a legal provision was required to extend the gestational termination period from 20 weeks to 24 weeks.

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 failed to achieve one of its primary goals of protecting pregnant women and empowering them by granting them the right to terminate their pregnancy at their own discretion.

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act has been criticized for failing to keep up with modern technology. It must be modified because it was introduced in 1971, when technology was still in its early stages. As a result, new provisions were urgently required.

- According to the act’s rules, the guardian’s written approval is required if the girl is a minor or under the age of 18, and above 18 if the lady is insane or lunatic.

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 has also been accused of adding to the already complex legal procedures. There is a need for more convenient and streamlined provisions.

Due to the limitations in the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971, an Amendment Act was introduced to fill the gaps. The Amendment Act was known as the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act of 2002.

MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY AMENDMENT ACT ,20025

This statute focused on most women employed in the private health sector. The Amendment Act took into account the following clauses and purposes:

- A committee that mostly operated at the district level oversaw deciding whether to authorize private enterprises to perform abortion services.

- The kind and magnitude of the pregnancy termination services, including the time and location, had to precisely adhere to the Act’s regulations; otherwise, greater penalties had been imposed.

- To address psychological conditions that did not qualify as mental disability, the term ‘lunatic’ was changed to mentally sick person.

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act of 2002 made modifications, but there was still a need to improve the environment of private hospitals that performed abortion services. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003 were enacted to regulate the operations of private hospitals.

MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY RULES, 2003

These rules laid down numerous provisions protecting the maternal health of the women and decreasing the numbers of mortality rates of both mother and the infant. Some of these provisions are as follows:

- Formation of a district-level committee to improve policy implementation and decision-making, consisting of at least one woman, gynaecologists or surgeons, local health professionals, and some members of non-governmental organisations.

- The Rules of Medical Termination, 2003 also cover the amenities, equipment, supplementary medically controlled technologies, and related services required to carry out the purpose and procedure of pregnancy termination.

- The guidelines further provide that the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is required to attend and inspect the site where abortions are performed to ensure sanitation and medically safe circumstances, as well as those in the surrounding areas.

- According to the Rules of Medical Termination, 2003, the Chief Medical Officer may prepare a report on the matter and present it to the committee in charge of approving the committee’s composition and licencing of the practice if, under certain conditions, he determines that the location where the practice of terminating pregnancies is performed is substandard.

As a result, the committee, satisfied with the current situation, has the option of suspending or even cancelling the owner’s permit to perform abortions. However, to respect the rule of law, the property owner is given the opportunity to speak and be heard by the committee prior to the issuance of the cancellation certificate.

Despite such rigorous laws, the condition of both the foetus and the pregnant lady remained unchanged. Illegal abortion practices continued to be prevalent. Incidents of infants being thrown in garbage cans and maternal fatalities were becoming more common, necessitating the passage of new legislation. As a result, new legislation was enacted in the form of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021.

MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2021

With rising technology and innovation in the healthcare sector, a need for better laws arose, which was met by the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act of 2021. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021 addressed a wide range of issues, including the right to privacy and improper gender assessment that led to female foeticide.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY (AMENDMENT) ACT, 20216

Dr. Harshvardhan Goyal of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare presented the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Bill 2020 to the House of People on March 2, 2020, following consultation with several experts, medical professionals, consultants, and other ministries. This bill revised the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, which deals with legal and permitted abortion. Furthermore, the proposed Bill attempted to streamline certain of the Act’s rules and regulations.

The Bill also aims to lengthen the legal abortion window from 20 to 24 weeks, allowing women to safely and securely terminate an unwanted pregnancy. It also intends to improve pregnant women’s privacy, gestational age, and safety measures.

The proposed legislation also seeks to implement current medical and health-care procedures that did not exist in the Act of 1971. Several public interest lawsuits were filed to end the lives of foetuses who were more than 20 weeks gestation. so that all women, even those who have been sexually attacked, raped, or have physical or mental problems, can stop their pregnancies via medical procedures.

MEDICAL TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY: STILL NOT A RIGHT BUT A PRIVILEGE

The introductory paragraph of the MTP Act, 1971 provides that the Act is solely designed for the termination of certain pregnancies7. Medical liberalization for termination of pregnancy is permitted in those indications which are stipulated in the Act. This is often accomplished by broadening the prior medical indication of rescuing a pregnant woman, to include medical and psychological morbidity or the risk of such morbidity, if the woman is compelled to carry an unwanted pregnancy to full term. For this purpose, Chief Justice KG Balakrishnan in Suchita Srivastava v. Chandigarh Administration8 has recognized the “Best Interest Test” which requires the court to ascertain the cause of action which would save the best interests of persons in question.

Merely because a woman having undergone a sterilisation operation became pregnant resulting in unwanted pregnancy, she cannot be compelled to bear the child as she will not be physically and emotionally compatible to raise a child. In these situations, as observed by Justice SP Garg in X v. State9, the prosecutrix is usually major who understands the consequences of her actions and if gives consent after considering the mental, social, economic problems which may arise in future then based on her express willingness she should be allowed to terminate the pregnancy. Considering the apparent danger to the lives of pregnant women, on more than one occasion Chief Justice SA Bobde and Justice L Nageswara Rao in Meera Santosh Pal v. UOI10 and Mamta Verma v. UOI11have allowed for the termination of pregnancy by observing:

“A pregnancy can be terminated only when a medical practitioner is satisfied that a continuance of the pregnancy would involve a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or of grave injury to mental or physical health or when there is a substantial risk that if the child were born, it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped.”

If the continuance of pregnancy is harmful to the mental health of a pregnant woman, then that is a good and legal ground to allow abortion. In Sk Ayesha Khatoon v. UOI the petitioner claims that it would be injurious to her mental health to continue with the pregnancy since there are several foetal abnormalities. Therefore, in the interest of justice and for safeguarding the life and liberty of the prosecutrix the court permitted to undergo medical termination of pregnancy at a medical facility of her choice.

One of the best cases in point which exemplifies that abortion is not a right rather a privilege is the situation of an unwanted pregnancy suffered by victims of sexual crimes. Rape is considered as one of the most barbaric actions which shake the common consciousness of society and generally becomes a cause of unwanted pregnancy. In such situations granting permission for termination of pregnancy beyond the statutory time limit becomes a therapeutic intervention rather than something to which they are entitled to as a matter of right. This line of argument is supported by ABC through her Guardian v. State of Maharashtra, Pramod A. Solanke v. Dean of BJ Govt. Medical College366 and X minor through her Guardian v. State of Madhya Pradesh where the mother (including minor girls) were victims of rape and they were allowed to undergo medical termination of pregnancy considering the apparent danger to their lives. This implies that the only recourse for terminating pregnancies due to rape that have crossed the twenty-four-week limit (as it stands today) is to get permission through a Writ Petition and to go through long and tedious judicial procedure. Clearly, the MTP Act, 1971 does not provide a basic right to induced abortion, but rather restricts the conditions under which women may obtain abortion services from certified medical practitioners. As a result, terminating a pregnancy becomes a therapeutic intervention or privilege, rather than a right, from a medical standpoint.

JUDICIAL REVIEW

Roe vs. Wade12

In this decision, the Supreme Court of the United States (“Court”) ruled that a woman’s right to abortion was guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment’s implicit right to privacy.

Jane Roe (“Appellant”) challenged the constitutionality of Texas State Penal Code Articles 1191-1194 and 1196 (together known as the “Texas Statute”), which criminalized abortions except those conducted to save the mother’s life. She claimed that the Texas Statute was unconstitutionally vague, infringing on her right to privacy as guaranteed by multiple sections to the United States Constitution.

The Court recognized that the right to privacy, which safeguards a woman’s right to abortion, is implied in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. However, this right was not absolute and must be evaluated against the State’s legitimate interests in controlling abortion. The Court declared the Texas Statute invalid. It ruled that due consideration for state interests varies throughout pregnancy, and that abortion laws must account for these variations. A restriction on a woman’s right to abortion would be permissible only if the State’s interests were substantial.

Mrs X and OR’s. v. Union of India (2017) 13

Facts of the case

In the present case, the petitioner was a 22-year-old woman who was around 22 weeks pregnant. The petition was filed under Article 32, thereby asking for allowing her to terminate her pregnancy. The petitioner contended that she was diagnosed with a condition known as bilateral renal agenesis and an hydramnios. It was also placed on record by her that the continuation of this pregnancy may endanger her life and that the foetus has no chance of survival.

Issue before the court

The issue before the court was to decide whether the petitioner should be allowed to terminate her pregnancy or not.

Judgment of the Court

The Supreme Court, after receiving the report from the medical board, allowed her petition, thereby permitting her to terminate the pregnancy, Relance was placed on the Suchita Shrivastava case, wherein it was held that the right to terminate pregnancy comes under the ambit of Article 21.

Nand Kishore Sharma and OR’s. v. Union of India (2005)

Facts of the case

The petitioners in the above-said case filed a PIL before the High Court of Rajasthan challenging Sections 3(2)(a) and (b) of the MTP Act, along with Explanations I and II provided in Section 3. The petitioners contended that these provisions infringe on the fundamental right of a woman protected under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Issue before the Court

The Rajasthan High Court had to decide whether these provisions under challenge were Inconsistent with Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Judgment of the Court

The Court, while dismissing the petition, held the sections under challenge to be valid. It emphasized the object of the MTP Act and opined that this law was enacted to make provisions relating to abortion as stringent and effective as possible. In no way were these provisions enacted to allow the blatant termination of pregnancy.

CONCLUSION

The MTP act is a crucial step towards recognising women reproductive rights in India. ongoing efforts are needed to address challenges, ensure implementation, and promote comprehensive reproductive healthcare. The mtp act 2021 is aglimmer of hope for women who wish to get safe abortions and for those who want to lawfully end their unplanned pregnancies. however, India still needs to do much more to curtail an eventually end the practice of illegal abortions. the government must make sure that all professional standards and regulations are followed nationwide in hospital and other health care facilities to allow the termination of pregnancies.

RFERENCES

- MEDICAL TERMINATION AND PREGNANCY (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2021, s. 5(A)

- Sharlien Kaur, Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971(July 9,2022)https://blog.ipleaders.in/medical-termination-of-pregnancy-act/

- Abortion Laws in India (Burnished Law Journal, 2020) accessed 23 May 2021

- . Introduction of MTP (Amendment) Act, 2021 in Changing Times: An Analysis by Vidhi Gupta, 3.1

- JCLJ (2022) 676

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act, 2021: nominally progressive or profoundly liberal? by Khushi Agrawal, 1.4 JCLJ (2021) 179

Footnotes

- https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/6832/1/mtp-act-1971.pdf ↩︎

- https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_parliament/2021/Medical%20Termination%20of%20Pregnancy%20Amendment%20Act%202021.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.drishtiias.com ↩︎

- https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/6832/1/mtp-act-1971.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.aiims.edu/aiims/events/Gynaewebsite/ma_finalsite/report ↩︎

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-news-analysis/medical-termination-of-pregnancy-mtp-amendment-act-2021 ↩︎

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971. Pmbl. ↩︎

- Suchita Srivastav VS Chandigarh Administration, (2009)9 SCC 1. ↩︎

- X vs State, (2013) SCC OnLine Del 1220. ↩︎

- MEERA SANTOSH PAL v. UOI, (2017) 3 SCC 462. ↩︎

- MAMTA VERMA v. UOI, (2018) 14 SCC 289. ↩︎

- https://privacylibrary.ccgnlud.org/case/roe-vs wade #:~: text=Ca se%20B rief,implicit%20in% 20the %20Fo urteenth%20Amendment ↩︎

- https://www.casemine.com/judgement ↩︎