Introduction

India has been historically a culturally diverse nation. Vedas, Jainism, Sangam literature, Buddhism, etc., have origins in India. The Varna system was basic segregation. The four varnas were Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaisya and Shudra. This varna was a flexible and heterogeneously distributed system. One can move upward and downward depending on one’s work. In this paper, I will try to explain how this framework became rigid and gave birth to the hierarchical caste system. I will also explain how the lack of adequate data has failed the objective of reservation even after being such a socially engineered tool.

I will also explain how the Mandal Commission was a game changer and will try to relate it to the latest caste survey. I will also demonstrate the evolution of the concept of reservation by the Supreme Court judgement and how the EWS judgement has diluted the concept of reservation. I will also explain how “the proportional share according to population is in direct conflict with the spirit of Constitution and is damaging the rights of scheduled caste and scheduled tribe provided explicitly by Constitution.

Who were Brahmans.

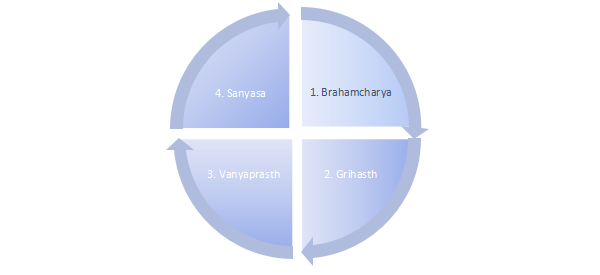

Ancient Indian philosophy assumes that a man has 100 years of lives and then categorically divides it into four parts i.e.: Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha and Sanyasa.

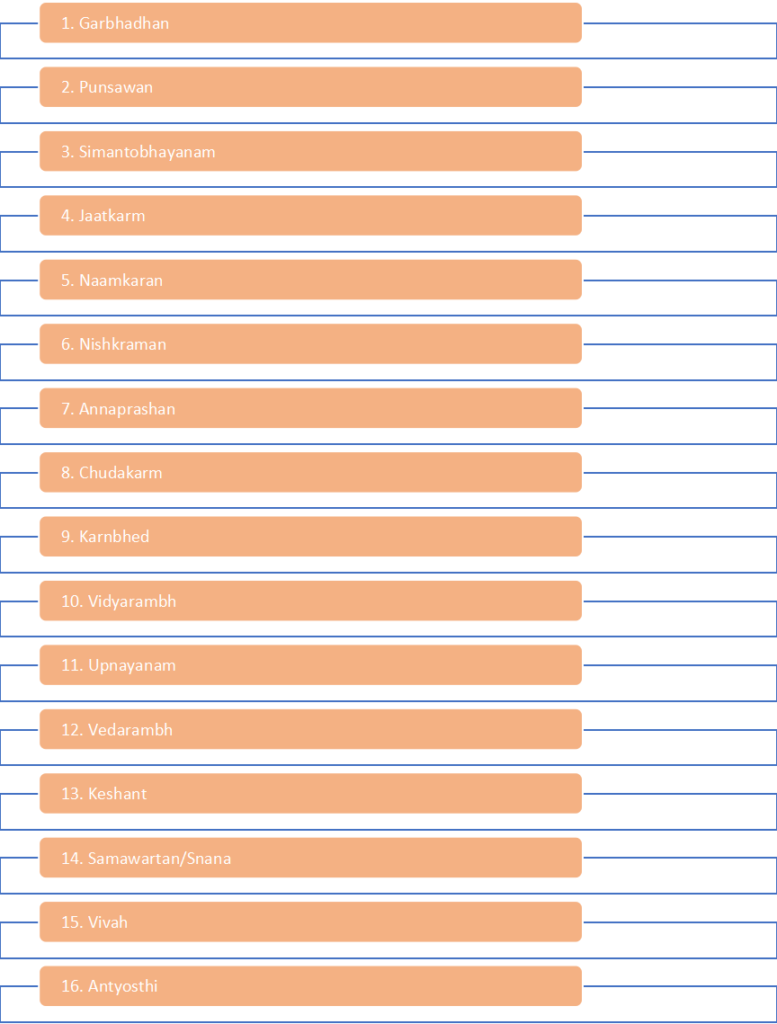

Then it says that everyone is born Shudra. There are a total 16 sanskaras a man has to pass through which are

Before Upanayanam, a child at 5 is expected to start his studies after worshipping Goddess Saraswati and Ganapati as well as his teachers. Upnayanam means going close to a guru and is different for different people. For brahman, the age limit is 8 years, which can be maximum extended to 16 years. For kshatriya, the age starts at 11 and can be extended to 22. Similarly, for vaishyas, the period begins from 12 years and can be extended to 24 years. Once guru decides who is cabable of which varna, he awards sacred thread or janeau.

Again, the quality of jananeu also varies from varna to varna. Brahmanas are awarded sacred thread of pure cotton whereas khstariya’s thread are made from hempen. Vaishyas wear woolen thread. a shudra is one who never goes close to guru and so he is not awarded any thread.

Later Vedic period & rigidity

Discovery of iron ensured rise of big kingdom. In India there were 16 Mahajanpadas, Magadh was mightiest of them. This rise of Kingdom also ensured a nexus of all three upper classes to form a collusion which ensured the varna system hierarchical. All the priestly class of different tribes declared themselves as Brahmans and others were non-brahmans. The system of distribution was heterogeneous and depended on geography. In south it was brahmans & non brahmans whereas in Bengal the segregation was Brahmans & Shudras. Only in North Indian belt the segregation was comprised of Four Varnas.

Constitution & Aftermaths

Article 15(1) of the Indian Constitution is a crucial provision aimed at preventing discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. It operates in tandem with Article 14, emphasizing that any unequal laws must be grounded in reason. The explicit prohibition of discrimination, particularly with the use of the term ‘only’ in Articles 15(1) and 15(2), signifies a disapproval of discrimination solely based on the specified grounds.

While Article 14 applies universally to citizens and non-citizens, Article 15(1) specifically covers Indian citizens. Additionally, Article 15(1) restricts certain grounds from forming the basis of classification. Notably, discrimination based on place of birth is prohibited, whereas residence is not covered by this prohibition.

Article 15(2) extends the prohibition of discrimination to places of public resort, prompting debate on whether access should be a legal right or a habitual practice. Despite challenges, personal laws remain immune from Fundamental Rights scrutiny, aligning with a policy approach to avoid interference in these systems.

Article 15(3) provides exceptions for making special provisions for women and children, aiming to eliminate socio-economic backwardness and empower women. The Supreme Court’s interpretation emphasizes the creation of job opportunities for women as an integral part of this provision.

Article 15(4) allows for special provisions for socially and educationally backward classes, Scheduled Castes, and Scheduled Tribes. The scope of Article 15(4) is broader than Article 16(4), encompassing various positive action programs beyond reservations. The determination of socially and educationally backward classes is left to the state, with the courts scrutinizing the relevance of criteria used.

In essence, Articles 15(1), 15(2), 15(3), and 15(4) collectively contribute to the framework of anti-discrimination and affirmative action in the Indian constitutional landscape, seeking to uphold the principles of equality and social justice. The provisions reflect a careful balance between preventing discrimination and addressing historical and social inequalities.

Balaji Case: Constitutional Dynamics in Reservation

The watershed Balaji case emerged as a pivotal juncture in constitutional jurisprudence following the enactment of the first Constitutional Amendment in 1951. Post-amendment, the Supreme Court grappled with the Balaji v. State of Mysore case, where the Mysore Government, under Article 15(4), issued an order reserving seats in state medical and engineering colleges for Backward and ‘more’ Backward classes based solely on castes and communities.

Flaws in the Mysore Order:

Sole Reliance on Caste: The Court critiqued the Mysore order for relying exclusively on caste without considering other pertinent factors. It emphasized that social backwardness primarily stems from poverty, necessitating a more comprehensive approach.

Flawed Educational Backwardness Measurement: The method employed to gauge educational backwardness drew censure. The inclusion of communities close to or above the state average was deemed invalid, as only those well below the average should be considered backward.

Invalid Classification: The Court objected to the order’s classification between ‘backward’ and ‘more backward classes,’ asserting that Article 15(4) did not envisage such a distinction.

Balaji’s Significance: The Balaji case underscored the peril of relying solely on ‘caste’ as a criterion for determining social and educational backwardness. It emphasized the critical role of economic backwardness as a more reliable indicator, noting that educational backwardness often traces back to social backwardness. The Court made a crucial distinction between ‘caste’ and ‘class,’ emphasizing the need for reservations under Article 15(4) to be reasonable and not undermine the foundational principle of equality enshrined in Article 15(1).

Post-Balaji Paradigm: Shifting Perspectives on Backwardness

In the aftermath of Balaji, judicial perspectives evolved, bringing about a nuanced understanding of caste, poverty, and backwardness.

- Chitralekha Case: A Departure from Caste-Centricity

In Chitralekha v. State of Mysore, an order that considered economic condition and profession, but not caste, to define backwardness, was deemed valid. This marked a departure from the exclusive reliance on caste, signaling an acknowledgment that determining social backwardness without explicit reference to caste is permissible.

- Re-emergence of Caste as a Determinant

However, recent judgments showcase a resurgence in the importance of ‘caste’ as a factor in assessing backwardness, deviating from the Balaji perspective. Courts acknowledged the existence of socially and educationally backward castes, underscoring that caste can be considered a ‘class’ of citizens. This shift raises concerns, as highlighted in Sagar, about perpetuating the caste system and impeding progress toward a casteless society.

- Refined Criteria and Periodic Review

In subsequent cases, such as K.S. Jayasree v. State of Kerala, the Supreme Court emphasized that social backwardness results from both caste and poverty. It clarified that neither caste nor poverty alone should be the sole determining factor. The judiciary further stressed that backwardness is not perpetual, granting the state the right to review classifications periodically. Indra Sawhney reiterated the need for reservations to be operated year-wise, with the state having discretion in setting reservation levels, considering legitimate claims and relevant factors.

Mandal Commission & Problem of Demography

Mandal Commission outlines the methodology and criteria employed by the Commission to identify socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs) in India. The Commission developed eleven indicators or criteria categorized under social, educational, and economic aspects. These indicators include castes/classes perceived as socially backward, reliance on manual labour, early marriage rates, female participation in work, educational attainment, economic indicators like family assets and housing conditions, and access to basic amenities. Each indicator was assigned a specific weightage based on its perceived importance, with social indicators given the highest weightage.

The Commission’s comprehensive approach aimed to capture the multifaceted dimensions of backwardness, considering social, educational, and economic factors. Social indicators were given a higher weightage as they were considered fundamental to understanding backwardness, followed by educational and economic indicators. The total score from all indicators added up to 22, and any caste scoring 50% or more (11 points and above) was categorized as socially and educationally backwards, while others were classified as ‘advanced.’ The Commission acknowledged the significance of economic indicators, emphasizing the interconnection between social, educational, and economic backwardness.

Chapter XII of the report focuses on identifying Other Backward Classes (OBCs) among Hindu communities. The Commission applied multiple tests, including stigmas associated with low occupation, criminality, nomadism, beggary, untouchability, and inadequate representation in public services. The methodology involved socio-educational field surveys, the 1961 Census Report, personal knowledge gained through extensive touring, and lists of OBCs notified by various State Governments. For non-Hindu communities, the Commission recognized the prevalence of the caste system and devised criteria for identifying OBCs among Christians, Muslims, and Sikhs.

Despite challenges in identifying OBCs among non-Hindus, the Commission proposed including untouchables converted to non-Hindu religions and occupational communities with Hindu counterparts in the OBC list. The Commission estimated that OBCs constituted approximately 52% of the Indian population, excluding Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

“12.19 Systematic caste-wise enumeration of population was introduced by the Registrar General of India in 1881 and discontinued in 1931. In view of this, figures of caste-wise population beyond 1931 are not available. But assuming that the inter se rate of growth of population of various castes, communities and religious groups over the last half a century has remained more or less the same, it is possible to work out the percentage that all these groups constitute of the total population of the country.”

In conclusion, the report highlights the systematic approach adopted by the Commission in identifying SEBCs and OBCs, considering a diverse set of indicators and criteria. The emphasis on social, educational, and economic factors reflects a holistic understanding of backwardness.

Social

A. Social

(i) Castes/Classes which are considered as socially backward.

(ii) Castes/Classes depending on manual labour for livelihood.

(iii) Castes/Classes in which at least 25% females & 10% of the males above the State average are getting married at age of 17 years or below in rural areas & at least 10% females and 5% males do so in urban areas.

(iv) Castes/Classes in which females’ participation in work is at least 25% or above of the State average.

B. Educational

(v) Castes/Classes in which total number of children belonging to the age group of 5-15 years & never attended school is at least 25% above the State average.

(vi) Castes/Classes in which the dropout rate of student belonging to the age group of 5-15 years is at least 25% above the State average.

(vii) Castes/Classes with a matriculation rate at least 25% below the State average

ECONOMIC

(viii) Castes/Classes with family assets averaging at least 25% below the State average.

(ix) Castes/Classes with a prevalence of families residing in Kutcha houses at least 25% higher than the State average.

(x) Castes/Classes where the primary source of drinking water is more than half a kilometer away for over 50% of households.

(xi) Castes/Classes with a number of households having taken consumption loans at least 25% above the State average.

The Commission’s effort to address challenges in identifying OBCs among non-Hindus demonstrates a nuanced approach to capturing the complexities of caste-based distinctions across different religious communities.

Percentage Distribution of Indian Population by Caste and Religious Groups

| S. no. | Name of the group | Total population percentage |

| I | Scheduled caste & Scheduled TribeScheduled Caste Scheduled Tribe | 15.057.51Total of A – 22.56 |

| II | Non-Hindu Communities, Religious Groups, etcB-1 Muslims (other than STs)B-2 Christians (other than STs)B-3 Sikhs (other than SCs & STs)B-4 Buddhists (other than STs)B-5 Jains | 11.19 (0.02)† 02.16 (0.44) † 01.67 (0.22) † 00.67 (0.03) †00.47Total of ‘B’ 16.16 |

| III | Forward Hindu Castes & Communities C-1 Brahmins (including Bhumihars)C-2 Rajputs C-3 Marathas C-4 Jats C-5 Vaishyas-Bania, etc. C-6 Kayasthas C-7 Other forward Hindu castes, groups | 05.52 03.90 02.21 01.00 01.07 01.88 02.00 Total of ‘C’ 17.58 |

| TOTAL OF ‘A’, ‘B’ & ‘C’ | 56.30 | |

| IV | Backward Hindu Castes & Communities D. Remaining Hindu castes/groups which come in the category of “Other Backward Classes | 43.70‡ |

| V | Backward Non-Hindu Communities | |

| E. 52% of religious groups under Section B may also be treated as OBCs. | 08.40 | |

| F. The approximate derived population of OtherBackward Classes including non-Hinducommunities | 52% (Aggregate of D and E, rounded)” |

†Figures in brackets give these population of SC & ST among the non-Hindu communities.

‡ This is a derived figure

Chapter XIII of the report presents various recommendations, particularly focusing on reservations in services. Considering the Supreme Court’s rulings that impose a cap of 50% on total reservations, the Commission put forth a recommendation for a 27% reservation in favor of Other Backward Classes (OBCs). This proposed reservation is in addition to the existing 22.5% reservation already in place for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). The intention behind these recommendations is to address historical disadvantages faced by OBCs and enhance their representation in public services.

Apart from reservations, the Commission also suggested several measures aimed at improving the overall conditions of these backward classes. These measures likely encompass a range of socio-economic initiatives, educational reforms, and affirmative action policies designed to uplift the status of OBCs. The specific details of these recommendations would be outlined in Chapter XIII, providing a comprehensive strategy for addressing the challenges faced by OBCs.

Moving forward, Chapter XIV of the report summarizes its findings, discussions, and recommendations. This section serves as a condensed version of the extensive information presented in the preceding chapters, offering readers an overview of the key points without delving into the detailed nuances of the Commission’s analysis.

In essence, Chapters XIII and XIV form a critical segment of the report, outlining the Commission’s stance on reservations for OBCs, proposing specific measures for their improvement, and providing a concise summary of the entire report. The recommendations presented in these chapters reflect the Commission’s commitment to promoting social justice, equality, and the well-being of historically marginalized communities in India.

BIHAR: CASTE SURVEY AND PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION

Recently, Bihar has become the first state to spend 500 crore rupees from its contingency fund to conduct a caste survey and all the Anganwadi workers were used for that purpose. It was challenged in Patna High court and Hon’ble Supreme Court which refused to entertain petition against it. The survey was conducted in two phases and total of 17 questions were asked from the people which included

- Identification of Family Member

- Paternal/Spousal Designation

- Relationship to Household Head

- Age (in years)

- Gender

- Marital Status

- Religious Affiliation

- Caste

- Status of Temporary Residency (location of work or study, whether domestic or international)

- Educational Attainment (from pre-primary to post-master’s level)

- Occupational Pursuits (encompassing roles in government or private sectors, organized or unorganized industries, self-employment, farming, labor in various sectors, skilled trades, student, homemaker, or unemployment)

- Possession of Computer/Laptop (inclusive of internet connectivity)

- Ownership of Motor Vehicle (categorized by two-wheeler, three-wheeler, four-wheeler, six-wheeler or more, tractor)

- Holdings in Agricultural Land (ranging from 0-50 decimals to 5 acres and above)

- Residential Property (including area details, such as 5 decimals to 20 decimals and above; flat ownership in a multi-storied apartment)

- Monthly Income from All Sources (varied from a minimum of ₹ 0 to ₹ 6,000 to a maximum of ₹ 50,000 and beyond)

- Residential Dwelling Condition (classifiable as permanent structure, thatched dwelling, hutment, or homelessness)

These data are not as promising as NHFS survey but shows the hope of fill the demographic gaps which are there in mandal commission so that SEBC who are on the almost equivalent to SC/ST can be identified and provided the benefit of reservation.

Conclusion

Supreme Court in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India has put a bar on the maximum limit of reservation to 50 percent nullifying 10% reservation based on economy. But Recently Supreme Court act of upholding EWS 10 percent reservation has opened a pandora box. One must understand reservation is an affirmative action and not a poverty elevation program. Government are using reservation to please their voters which ultimately is leading to loss of opportunity in government sector for a particular class. Poverty and illiteracy should be countered by different schemes and bar of 50 percent should be raised in rare cases only.