Introduction

The advent and swift evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has drawn out a number of legal, ethical, and philosophical issues, one of the most significant being whether AI can be recognized as an inventor. As AI keeps on developing with time and gets more creative, it can generate new ideas and even solve highly technical problems. This is especially applicable to intellectual property (IP) law, such as patent systems around the world, because IP, particularly patent statutes and laws, were created under the belief that inventors are human.

The question of whether AI inventors should seek patent protection for their discoveries is not merely theoretical; it is already being debated in courts and patent offices all over the world. Different countries have taken a position about whether inventions by AI merit patentability and, if so, whether an AI can be considered as an inventor. Up until now, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and others, have all maintained that only natural persons can be recognized as inventors under current patent laws. Conversely, countries like South Africa and Australia are adopting a far more “open-minded” stance on the concept of AI-generated patents, which unavoidably generates more debate regarding the necessity for legislative reform.

As an upcoming technology hub, this issue has also presented a challenge in India. With its thriving AI sector and growing number of AI-based innovations, the nation has the necessity to confront how its laws allow for AI-created inventions. Should India follow the international trend of limiting inventorship to human inventors, or should it instead take a softer approach in understanding AI as a valued contributor to innovation?

This article explores the evolving debate on whether artificial intelligence (AI) can be recognized as an inventor under existing patent laws. It examines the legal, philosophical, and ethical implications of AI-generated inventions. The discussion highlights how different jurisdictions, including the U.S., European Union, U.K., Australia, South Africa, and India, have addressed AI inventorship, with most reinforcing the requirement that an inventor must be a natural person. Furthermore, the article delves into India’s legal framework, the challenges of integrating AI within intellectual property laws, and potential policy reforms to adapt to the rise of AI-driven innovation. Ultimately, it raises critical questions about the nature of creativity, ownership, and the need for legal evolution in the face of rapidly advancing technology.

Inventor vs. Inventorship: A Conceptual Distinction

An invention, in legal terms, is usually something novel and unique that involves creativity and can be practically applied in industry. Patent laws, following the guidelines set by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), generally require that an inventor be a real person. This rule is meant to ensure that patents go to individuals or entities that have demonstrated human ingenuity.

However, with the onset of artificial intelligence—particularly the sophisticated generative and deep learning models that can develop creative solutions independently—this conventional notion of inventorship is being challenged. AI systems such as DABUS (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience)1, developed by Stephen Thaler, have been at the forefront of this debate. DABUS has generated novel ideas, such as a unique food container with fractal geometry and a neural flame device, prompting discussions on whether AI can rightfully claim inventorship.

The altercation over whether AI can be considered as an inventor primarily comes down to understanding the difference between an “inventor” and “inventorship.” Traditionally, an inventor is someone who comes up with an idea and brings it to life. Whereas, inventorship is a legal status that determines who has the right to hold patents and protect their intellectual property. Under existing laws in countries such as the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, inventorship is strictly human-based. This implies that, at least for now, only individuals—not AI—are legally recognized as inventors.

AI, as an independent system, adds complications to this issue. It doesn’t have legal rights or intentions like a human does, yet it can come up with inventions that are clearly different from those created by people. This has initiated a global discussion on whether existing legislation needs to be modified to account for inventions created through AI. Various courts in jurisdictions have decided that patents cannot be issued to AI, further strengthening the belief that inventorship has to be human-based. For instance, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)2 and the European Patent Office (EPO)3 have both denied applications listing AI as an inventor, asserting that only natural persons can be recognized in this capacity.

Legal Perspectives on AI as an Inventor

United States

In the U.S., the Patent Act mandates that an inventor must be a “natural person.” In the case of Thaler v. Hirshfeld4, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected the patent applications which listed DABUS as the inventor. The Federal Circuit upheld this decision, emphasizing that AI cannot be legally recognized as an inventor.

European Union

Similarly, the European Patent Office (EPO) has ruled that under the European Patent Convention (EPC), only natural persons can be recognized as inventors. This stance was affirmed in its decisions on applications listing DABUS as the sole inventor5.

United Kingdom

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and the English and Welsh High Court have insisted that patent law in its present form does not allow for AI to be identified as an inventor. Making changes in the Legislations would be necessary to change this stance.

Australia and South Africa

While Australia initially ruled in favor of AI inventorship, recognizing DABUS as an inventor in Thaler v. Commissioner of Patents6, this decision was later overturned by the Full Federal Court7. In contrast, South Africa became the first country to grant a patent listing AI as an inventor, although its patent system lacks a substantive examination process, making it an outlier in the global debate.

The Indian Legal Framework on AI-Generated Inventions

Current Patent Law in India

The Indian legislation concerning inventions is primarily governed by the Patents Act of 1970, which outlines the criteria for patentability, which include novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability. However, the Act does not explicitly address inventions autonomously created by artificial intelligence systems, leading to challenges regarding inventorship and patent eligibility. Section 6 of the Act specifies that a patent application must be made by the “true and first inventor,” a term traditionally understood to refer to a natural person. This view has led to the question of whether of AI systems should be recognized as inventors. Furthermore, Section 3(k) excludes “a mathematical or business method or a computer programme per se or algorithms” from patentability, which can impact the eligibility of AI-related inventions, especially those heavily reliant on software and algorithms8.

Despite these challenges, the Indian Patent Office has shown some flexibility in assessing computer-related inventions by considering the technical contribution and effect of the claimed subject matter. In the case of Ferid Allani v. Union of India9, the Delhi High Court recognized that inventions showing a technical effect or contribution are not precluded from patentability, although they may be based on computer programs. This view is that AI-related inventions may be patentable if they represent a technical solution to a technical problem.

However, the concern of inventorship remains unresolved, as current Indian patent law does not integrate non-human inventors. As AI is also developed by a human, this issue gets further complicated as to who will take the liability of the patent and who do the monetary benefits go to. This gap has prompted debate on whether legislative reforms are necessary to counter the particular challenges that inventions made by artificial intelligence present and ensure that the patent system still supports innovation in this day and age of artificial intelligence.

AI and Intellectual Property Policies in India

As AI systems keep on becoming more proficient at producing original concepts, procedures, and even creative works, the topic of whether AI can be considered as an inventor becomes increasingly important in the field of intellectual property law. The base of traditional patent laws globally is the idea that being an inventor is purely a human activity that calls for qualities like intentionality, inventiveness, and problem-solving that are hard to assign to non-human entities. While India does not currently have any written regulations that specifically regulate AI, artificial intelligence systems are treated like software, which provides only a restricted level of protection in comparison to patents.

Since only people or legal individuals are permitted to own intellectual property rights under the current legal framework, AI systems cannot be recognized as authors or inventors. The bottom line is that AI is also developed by a human. India’s intellectual property (IP) policy on AI remains in development, walking the tightrope of innovation and legal protection.

Indian law does not, at present, consider AI as an author or inventor, instead insisting on human attribution for patents and copyrights. The government is considering AI-specific rules, including data protection, patentability of inventions created through AI assistance, and concerns around liability. Recent dialogue focuses on responsible AI development while also ensuring equitable use and protection of creators’ rights. With increasing AI adoption, India can introduce more definite regulations to tackle ownership, responsibility, and marketability of AI-created works.

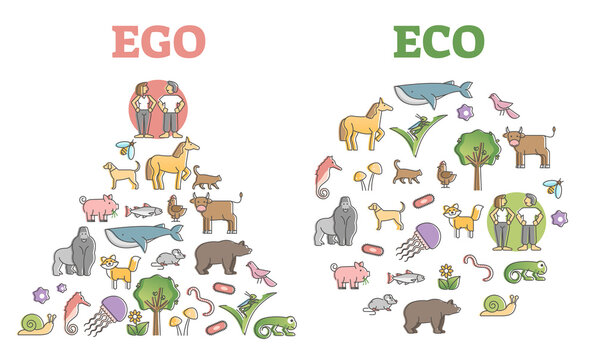

Ethical and Philosophical Implications

Conventional notions of ownership, creativity, and legal acceptance are brought into question by the capacity for AI to be an innovator. Human creativity, spurred by intentionality and the ability to conceive of complex, abstract issues in fashion that robots are allegedly incapable of doing so, has long been attributed with creation. However, the subject of whether artificial intelligence (AI) can be regarded as an inventor has become a compelling legal and philosophical issue with the development of refined AI systems that can produce original answers. The question of whether AI-generated ideas should be patentable and, if so, who should be given credit as the true inventor—the AI system, its creators, or the organisation that owns the AI—has come up in contemporary times.

The AI system DABUS, which was named as the inventor on patent applications in several jurisdictions but was denied by numerous patent offices for not meeting the legal definition of an inventor, is an example of how this argument has practical ramifications. Because AI does not have the concept of moral responsibility or consciousness, awarding inventorship to it poses ethical concerns regarding liability. Moreover, remitting inventorship to AI could disturb existing intellectual property systems, and it might unnerve human innovation or lead to monopolistic ownership by the firms that hold the AI systems.

The more profound philosophical implications are the subject of further controversy among philosophers: does AI truly “invent,” or does it merely creatively reconfigure information which is already existing? Some hold that purpose and comprehension—attributes AI presently does not possess—are essential to genuine creation. Others suggest that legal systems should adapt to account for AI’s input and that the demarcation line between human-created innovation and AI-created innovation is arbitrary. Legal and ethical frameworks must address the important question of whether inventorship is fundamentally a human quality or whether AI can rightfully claim a place in the creative process as it develops.10

Future Directions and Recommendations

India, as an emerging leader in AI-driven innovation, must take proactive steps to address the legal ambiguity surrounding AI-generated inventions. Some potential approaches include:

1. Legal Clarity on AI as an Inventor

India should establish clear legal guidelines on whether AI can be recognized as an inventor under patent law instead of leaving it as a grey area. Amendments to the Indian Patent Act may be needed to address AI-generated inventions.

2. AI and Intellectual Property (IP) Framework

There should be a balanced approach to AI-generated inventions, which ensures fair credit to AI developers and human collaborators or maybe consider a separate category for AI-assisted inventions within the IP framework.

3. Ethical and Policy Considerations

Guidelines should be established on AI’s role in innovation to prevent misuse or monopolization. Along with encouraging transparency in AI-driven research and development.

4. Strengthening AI Regulations

Forming a regulatory body to oversee AI-related patents and ensure compliance with global standards. This body should also monitor AI’s impact on employment and creativity in research fields.

5. International Collaboration and Standardization

Participate in global discussions on AI and intellectual property rights and also align India’s policies with WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) and other international bodies.

6. Public Awareness and Stakeholder Engagement

Conduct public consultations and stakeholder discussions on AI’s role in invention. Educate businesses and researchers on AI-related IP laws and best practices.

Conclusion

The issue of whether AI qualifies as an inventor is now a serious legal and philosophical one rather than a theoretical one. Conventional frameworks of intellectual property law are being put to the test as AI systems continue to produce innovative concepts and technological breakthroughs. Even though many countries, including India, still uphold the rule that only natural individuals are capable of invention, the quick development of artificial intelligence necessitates a review of these standards. A balanced strategy that encourages innovation while maintaining accountability and ethical considerations is necessary for India to navigate this complicated challenge.

Public debate, regulatory frameworks, and legal clarity will all be important factors in determining India’s position on AI inventorship. India can establish itself as a leader in AI-driven innovations by taking inspiration from international examples and modifying laws to fit its own innovation ecosystem. AI will eventually be included into the creation process, but whether or not it should be given inventorship depends on society preparedness, ethical considerations, and legal interpretation. In order to ensure that innovation is both promoted and appropriately controlled in the era of artificial intelligence, our rules and viewpoints must advance along with technology.

Footnotes

- https://brandequity.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/digital/meet-dabus-the-worlds-first-ai-system-to-be-awarded-a-patent/85149000 ↩︎

- https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2024/02/can-ai-inventions-be-patented-the-uspto-speaks ↩︎

- European Patent Office. “EPO Decision on AI Inventorship in Patent Applications.” European Patent Office, 2020 ↩︎

- Thaler v. Hirshfeld, 558 U.S. (2021) ↩︎

- European Patent Office. “EPO Refuses DABUS Patent Applications Designating AI as Inventor.” European Patent Office, 2021 ↩︎

- Thaler v. Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCA 879 ↩︎

- Commissioner of Patents v Thaler [2022] FCAFC 62 ↩︎

- The Patents Act, 1970, No. 39, Acts of Parliament, 1970 § 3(k), § 6 (India) ↩︎

- Ferid Allani v. Union of India, (2020) 81 PTC 489 (Del.) (India) ↩︎

- “Ethical and Philosophical Implications of Granting AI Inventorship.” Journal of AI Ethics and Law, vol. 12, no. 3, 2023, pp. 45-67 ↩︎