ABSTRACT

“When pain becomes life, mercy becomes love.” Euthanasia remains one of the most contested issues regarding legalization. This study provides a comparative legal analysis of euthanasia across different nations, with a special focus on India. It traces the historical evolution of euthanasia from ancient medical practices to modern-day ethical and legal interpretations. This study examines the Indian constitutional framework under Article 21 and significant the Supreme Court’s decisions, including Aruna Shaunbaug vs UOI and Common Cause vs UOI, and the gradual recognition of the “right to die with dignity.” It also contrasts India’s cautious legal stance with the more liberal approaches of the Belgium, Netherlands, Canada, and certain U.S. states, highlighting how different legal systems balance individual autonomy, medical ethics, and societal values. This study concludes by offering international recommendations to ensure that any legalization of euthanasia is guided by compassion, dignity, and stringent safeguards against abuse.

Keywords: Euthanasia, Right to Die with Dignity, Article 21, Comparative Legal Analysis, Judicial Interpretation.

Introduction

The term “euthanasia” was first employed in the seventeenth century by the English philosopher Sir Francis Bacon. It comes from the Greek terms EU, which translates to “good,” and Thanatos, which translates to “death.” Euthanasia consists of intentionally terminating someone’s life to relieve their suffering1. It entails administering drugs specifically aimed at inducing a painless death, especially in situations of terminal illness, intolerable suffering, or when a significant physical or mental disability has made life without value2.

This implies ending someone’s life for a righteous reason. For someone enduring a prolonged struggle with an incurable disease, death might appear to be the sole solution when there seems to be no escape from the suffering. As a result, euthanasia is the intentional termination of a patient’s life to alleviate their pain. Euthanasia allows an individual to die swiftly and with honour rather than experiencing an agonizing and prolonged demise. In other words, it is the intentional ending of a terminally ill patient’s life using specific techniques aimed at alleviating their intense pain and suffering.

Euthanasia falls into two categories: Active and Passive. Active euthanasia entails taking intentional steps to end a person’s life, including giving them a fatal injection. Conversely, passive euthanasia is the practice of stopping medical interventions that could extend life and letting death happen organically.

History

Euthanasia has a long and complex history in the Netherlands. Before Hippocrates, it was a common medical practice for physicians to end the lives of hopeless patients without consent. Hippocrates opposed this, emphasizing trust between doctor and patient, leading to the line in Hippocratic Oath- “I will give no deadly medicine to anyone if asked, nor suggest any such counsel.” The practice took a dark turn during Nazi Germany’s Aktion T4 program, where thousands, including children and the disabled, were killed under the guise of “mercy deaths.” These killings, carried out under medical supervision, were acts of murder rather than compassion, sparking global ethical debates on mercy killings.

Discussions on end-of-life rights eventually resulted in their legalization in some areas. The Netherlands legalized euthanasia in 2001 after Australia’s Northern Territory did so in 1996. Strict regulations ensured that decisions were made voluntarily, intelligently, and under medical supervision.

While euthanasia began as an ancient medical practice and has been misused throughout history, its modern form is rooted in compassion, dignity, and the individual’s right to choose.3

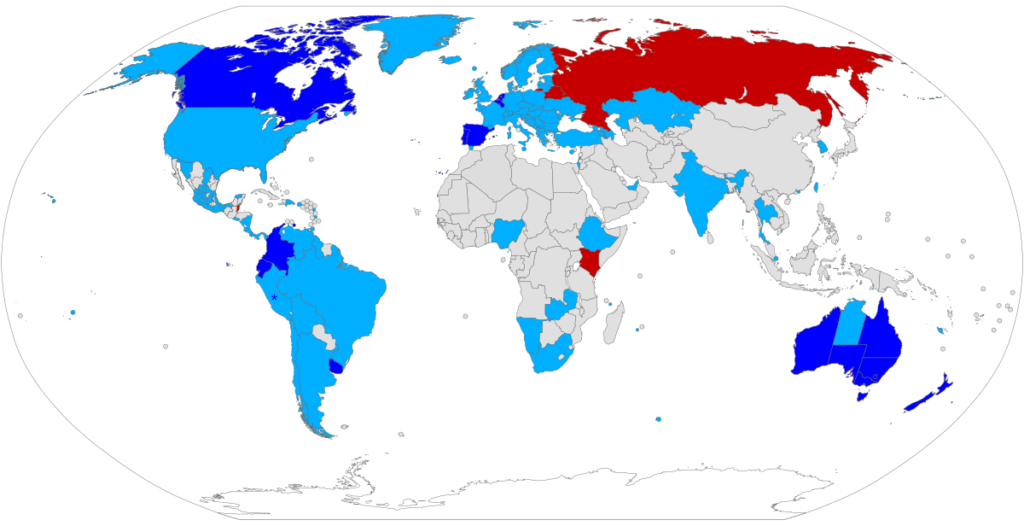

Legal Frameworks Governing Euthanasia in Different Countries

INDIA

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution specifies that an individual’s life or personal liberty cannot be deprived without adhering to the legal procedures. The right to health, livelihood, privacy, shelter, and dignity are just a few of the rights that the Supreme Court has construed this clause extensively to cover. In K.S. Puttaswamy vs Union of India4, The Court reaffirmed that human dignity is a key element of Article 21. The “right to die” isn’t included in the “right to life,” yet it entails the right to exist and the right to die with dignity, especially for those at the end of life with no prospects for recovery.

In P. Rathinam v. Union of India (1994)5, The IPC Section 309, which criminalizes attempted suicide, was challenged by the petitioners as unconstitutional. They claimed that the clause is against the Constitution’s Articles 14 and 21. The Supreme Court’s two-judge decision declared Section 309 IPC unconstitutional, determining that the right to life as stated in Article 21 encompasses the right to escape an undesirable or coercive existence.

Later, in Gian Kaur vs State of Punjab (1996)6, The appellants, who were found guilty of “aiding and abetting suicide under Section 306 of the Indian Penal Code”, contested the law’s validity, claiming that it went against Article 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court rejected this claim, concluding that the right to life does not encompass the right to euthanasia. The Court clearly expressed that Article 21 safeguards human dignity, encompassing the right to lead a respectable life until death occurs naturally, but not the right to end one’s own life.

The Court differentiated between the right to die and any type of unnatural death, even while it acknowledged that a dignified death may be a component of the right to live with dignity in situations involving terminal illness or when the process of natural death has started. Although it left open the issue of non-voluntary passive euthanasia for future consideration, it upheld the constitutionality of Section 309 IPC and declared that assisted suicide and euthanasia were both prohibited in India.

The question of euthanasia was first directly addressed by the Supreme Court in Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaugh v. Union of India (2011)7. Aruna Shanbaugh, a nurse from Haldipur, Karnataka, was brutally assaulted by a hospital ward boy in 1973 during working time at King Edward Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. The assault left her in a condition of sustained vegetation for decades following incident. In 2011, after 37 years of being in that condition, the Supreme Court considered a petition filed by journalist Pinky Virani, who requested permission for euthanasia for the patient. The Court appointed a medical panel to assess Aruna’s condition.

Ultimately, the Court rejected the plea but decided that passive euthanasia might be permitted in exceptional cases under strict legal supervision, whereas active euthanasia remained prohibited. The Court also recommended that the criminalization of attempted suicide under the IPC be reconsidered and the punishment removed from it.

In the case of Common Cause vs Union of India (2017)8, The Supreme Court’s Constitutional Bench ruled that a “meaningful existence” must include the “right to die with dignity.” This historic decision upheld the Aruna Shanbaug order from March 2018 and resulted from a Public Interest Litigation brought by the NGO Common Cause in 2005. The Court published thorough rules for the execution of living wills and acknowledged their validity for terminally ill people. When a person has an irreparable illness, they can communicate their wishes for euthanasia through a living will. The doctors and the patient’s family have the last say over whether to stop medical care in the absence of such a document. The Court emphasized that physicians must verify a patient’s incurable condition before withdrawing life support and explicitly prohibited any active measures, such as administering drugs, to hasten death.

NETHERLANDS

The Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act (2001) in the Netherlands allows for physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. As long as informed consent is granted and the doctor complies with stringent legal and procedural standards, the law allows patients who are in excruciating pain and have little possibility of recovery to freely seek euthanasia. The Dutch system permits doctors to carry out euthanasia without judicial intervention as long as all legal requirements are satisfied, in contrast to India, where even passive euthanasia necessitates court supervision and numerous medical evaluations. Therefore, India’s legal approach is more limited and stresses strict protections to prevent misuse, whereas the Netherlands favours patient liberty.9

BELGIUM

The Belgian Euthanasia Act of 2002 made euthanasia legal in Belgium, allowing for both voluntary and, under certain circumstances, nonvoluntary euthanasia. In contrast to Indian law, Belgian law enables euthanasia for minors under stringent precautions. Belgium gives doctors more freedom to carry out euthanasia as long as they follow accepted medical and ethical guidelines, whereas India’s system requires judicial approval and a thorough medical assessment before allowing passive euthanasia. Overall, India continues to take a cautious approach, limited to passive euthanasia, whereas Belgium takes a more progressive attitude, acknowledging euthanasia as an individual right.10

CANADA

In 2016, Canada endorsed Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) following the significant Supreme Court decision in Carter v. Canada (2015)11, which acknowledged the entitlement of individuals with serious and terminal illnesses to seek medical help to conclude their lives. Unlike India, where euthanasia is restricted to stopping life-sustaining care in severe situations, Canada’s MAID system permits both active euthanasia and assisted suicide under certain conditions. This illustrates a more compassionate and patient-focused method, emphasizing the individual’s right to choose alleviation from unbearable distress.12

UNITED STATES

Every state in the US forbids active euthanasia. However, the District of Columbia, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, and, most recently, Delaware (2025) permit physician-assisted suicide or medical assistance in dying under stringent limitations. Because of the 2009 State Supreme Court decision in Baxter v. Montana, which acknowledged legal protection for doctors helping terminally ill individuals end their lives, the practice is allowed in Montana without the need for legislation.13

Recommendations on Legalizing Euthanasia Worldwide

- The right to a dignified life and death dignity should be recognized by international law, particularly for people who are in excruciating and irreparable pain.

- Euthanasia should only be available to competent adults diagnosed with a terminal, incurable, or severely debilitating medical condition that causes intolerable suffering.

- The patient’s request must be made voluntarily, repeatedly, and without external pressure, ensuing genuine consent.

- At least two independent physicians should confirm the diagnosis, prognosis, and patient’s mental capacity before euthanasia is approved.

- A mental health evaluation should be mandatory to ensure that the request is not the result of treatable depression or emotional distress.

- A reasonable time gap between the initial request and euthanasia is required to confirm the patient’s consistent decision.

- “Living wills” or “advance directives,” which let people express their preferences for end-of-life care, should be legally recognized in all countries.

- A judicial body or ethics committee should review each case to prevent misuse and ensure that all legal conditions are satisfied.

- No medical professional should be compelled to perform euthanasia; participation must remain voluntary for physicians and nurses.

- Governments must ensure that euthanasia is never considered an alternative to inadequate health care. Instead, they should prioritize universal access to effective palliative and hospice care to alleviate suffering and uphold patient dignity.

- All euthanasia cases should be documented, reviewed, and reported to an independent national authority for monitoring and accountability.

- Legal frameworks must include strict penalties for coercion, falsified consent, and misuse of euthanasia provisions.

- Countries should promote open dialogue on end-of-life ethics to build societal understanding and reduce the stigma surrounding euthanasia.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) or the United Nations could develop global standards to guide nations in choosing to legalize euthanasia.

- Euthanasia legislation should be periodically reviewed to incorporate medical, ethical, and social developments, and to ensure the continued protection of human rights.

Conclusion

At the intersection of ethics, legislation, and human rights, euthanasia remains one of the most ethically and legally intricate subjects in modern society. Countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Canada have accepted euthanasia as a facet of personal freedom and the right to die respectfully, while India remains cautious, permitting only passive euthanasia with judicial oversight. The growing recognition that dignity in dying holds equal significance to dignity in living is evident in the evolution of Indian legal principles from Gian Kaur to Common Cause.

Globally, the debate must move beyond moral polarization toward a compassionate legal framework that protects both individual choice and societal ethical standards. Legalizing euthanasia worldwide requires uniform safeguards, transparency, informed consent, and strong medical and judicial oversight. Ultimately, the goal is not to promote death but to affirm the humane principle that every individual deserves to live and die with dignity, free from unnecessary suffering and pain.

References

- https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/euthanasia-and-assisted-suicide

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320829903_Euthanasia_A_Brief_History_and_Perspectives_in_India

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/91938676

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/542988

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/217501

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/235821

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/184449972

- https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12393

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/euthanasia#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20active,most%20recently%20Delaware%20(2025)

Footnotes

- https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/euthanasia-and-assisted-suicide/ ↩︎

- Dr. Parikh C.K, Textbook of Medical Jurisprudence’s Forensic Medicine and Toxicology ,6th edition, New Delhi, CBS Publishers &Distributions. ↩︎

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320829903_Euthanasia_A_Brief_History_and_Perspectives_in_India ↩︎

- K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors. (2017)10 SCC 1 ↩︎

- P. Rathinam v. Union of India (1994)3 SCC 394 ↩︎

- Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab (1996)2 SCC 648 ↩︎

- Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaugh v. Union of India AIR 2011 SC 1290 ↩︎

- Common Cause v. Union of India (2018) 5 SCC 1 ↩︎

- Pralong, J. “Safeguarding Euthanasia Laws: The Case of the Netherlands and Belgium.” Bioethics, 31, no. 8, 2017, pp. 585–590 ↩︎

- Chambaere, K., et al. “Euthanasia in Belgium: Trends in the Last Five Years (2009–2013).” JAMA, 313, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1023–1030 ↩︎

- Carter v. Canada (attorney general), 2015 SCC 5, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 331 ↩︎

- Chauvin, J.P., and J.F. Mayer. “Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada: Legal, Ethical, and Clinical Considerations.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188, no. 9, 2016, pp. 626–627. ↩︎

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/euthanasia#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20active,most%20recently%20Delaware%20(2025). ↩︎