https://t4.ftcdn.net/jpg/04/17/64/77/360_F_417647727_rzoqKoBxHdXawjGRtBgmwq2YsyhNHpdy.jpg

Introduction

The problem of the moral status of human and non-human animals has become perhaps the most pressing place where ethical reflection meets the broader brute reality of the contemporary world. Things like factory farming, animal testing, wildlife preservation, climate change and city animals pose problems to traditional moral frames that put people first over all other life forms. As Peter Singer notes, the philosophical debate between human- and biocentrism is key to this ethical discussion. Anthropocentrism situates humans as the moral center of the world, with nature and animals being treated instrumentally in relation to their use value for humans. It develops instead a biocentric morality that acknowledges inherent value in non-human life, regardless of human usefulness.

Here, I explore two opposing ethical frameworks in animal ethics – anthropocentrism and biocentrism. Adopting a comparative and historical perspective, it also considers their philosophical background, impact on animal welfare and environmental ethics, and practical relevance in the context of the current socio-legal system. Through these textual findings, the essay contends that while anthropocentrism as a guiding framework has historically been responsible for structuring dominant human–animal relations, biocentrism emerges as an alternative and more ethical orientation in an age when ecological collapse and awakening to ethics is on the horizon.

Understanding Anthropocentrism

Human centeredness, that which places human beings at the center of moral concern, is known as anthropocentrism (from the Greek what means: human and center). Within such a framework, nature and its nonhuman inhabitants are valuable instrumentally as means to human ends (survival, convenience, progress). Moral responsibilities to animals are only recognized when they affect human well-being.

Philosophical Foundations

Classical Greek philosophy specifically, Aristotle’s Great Chain of Being that placed humans at the top (‘great or higher up’ means God at the third point from below) of a hierarchy of life forms because they were capable of reasoning (see Aristotle,translated. 1998). This hierarchy was further enshrined in Judeo-Christian theology which gave humans “dominion” over animals (Genesis 1:26), a phrase commonly interpreted as moral license to exploit animals for human purposes.

Descartes Advance in lighting and factory production further disassociated animals from human life, enabling them to become objects for anthropocentric use (Parkin 2007).In the western world, René Descartes was particularly influential for forming this view of the animal as merely an automaton a being who is unable to think or feel (Descartes 1641/1984). This mechanistic outlook validated vivisection and experimentation, influencing scientific standards for a long time.

Anthropocentrism in Animal Ethics

The environmental equivalent of human-focused ethics is certainly as much in evidence: Anthropocentrism can be seen at work, for instance, when one observes practices like:

- Factory farming justifiable by human appetite for animal products

- Supported animal experiments in the name of “progress”

- Use of wildlife for tourism and financial gain

Even good welfare-based strategies, such as those embodied in humane slaughter laws, remain largely anthropocentric since they aim to minimize animal suffering while ignoring human claims of entitlement to use animals.

In contrast, weak anthropocentrism permits concern for animals, but only to a certain extent, in the form of kindness and welfare not pertaining to animals but rather from them (Norton 1991). This model pervades policy regimes around the world.

Biocentrism: Expanding the Moral Community

Biocentrism opposes the human-centered perspective, that all living things have value in themselves. Biocentrism, like anthropocentrism but probably worse than the latter, does not give humans any special status simply because they are humans. Rather, it is possession of life that confers moral worth.

Philosophical Origins

Biocentric thought is rooted in Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism and Jainism, which promote a philosophy of ahimsa or “non-harm” to all beings. In Western thought, the basis of biocentrism emerged as an “ecological” approach a reproach in 20th century environmental ethics.

Albert Schweitzer’s idea of “reverence for life” gave a new and significant direction to biocentric ethics, stressing moral responsibility toward all living creatures (Schweitzer, 1965). Later, Paul W. Taylor systematized biocentrism in respect for Nature (1986), maintaining that all creatures are “teleological centers of life” striving after their own well-being.

Biocentrism in Animal Ethics

Biocentrism requires human representation to be rethought at a foundational level when it comes to humans and animals. It challenges:

- The morality of animal slaughter for food

- Animals as subjects of experiment

- Human dominance over ecosystems

According to this approach, animals are not a means to an end (a human end) but are moral subjects deserving respect. Justifying an ethical decision requires weighing interests without taking for granted the ranking of our species.

Anthropocentrism v Biocentrism: A Cross-Analysis

Moral Status of Animals

The first is anthropocentrism, which views animals as having instrumental value, while the second (biocentrism) grants them intrinsic value. Anthropocentrism is indifferent to animal suffering, except in cases where it can be shown to have the power to affect human enjoyment; biocentrism makes animals’ well-being matter in and of itself.

Ethical Decision-Making

Expansion of the relationship Some critics, such as Oscar Horta, have pointed out that these arguments can be based around anthropocentric justifications, which is based on benefits to humans even where this requires causing harm to other animals on a massive scale (e.g. in industrial farming). Biocentric morality implies moral caution and consideration of least harm over species barriers.

Legal and Policy Implications

Most legal systems remain anthropocentric. Laws protecting animals usually define abuse as offensive to humans, not to the animal. New judicial developments, however the recognition of animals as legal persons or sentient beings indicate a transition towards biocentric justification.

Anthropocentrism, Speciesism, and Power Hierarchies

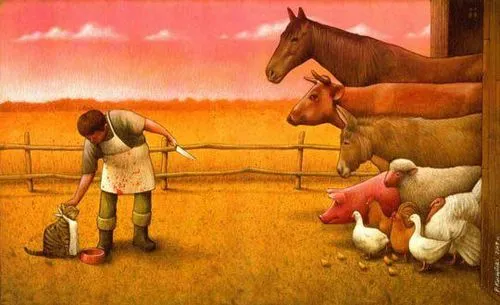

A critical ethical limitation of anthropocentrism is its close association with speciesism, a concept popularized by (Singer, 1997). Speciesism works in the same way as racism and sexism, i.e. using certain biological differences to deny moral consideration. This philosophy makes speciesism a “natural” state of affairs because what is best for other animals is always subordinated to what is best for humans (meaning anarchism fails by default every time.)

This hierarchy of thought creates power structures that maintain humans as moral commandors and animals as moral non-actors. Quality These hierarchies under gird attention-community and exist in social institutions such as agriculture, education, religion, science and more. For example, laboratory animals are frequently depersonalised or deanimated by being rendered into mere numerical units or subjects of investigation and not treated as sentient beings. Biocentrism dissolves these hierarchies by questioning the moral legitimacy of domination, and claiming that power is not an ethical principle.

In addition, postcolonial and feminist scholars have made connections between anthropocentrism and other forms of subordination, asserting that the same modes of thought that rationalize animal exploitation have historically been used to subordinate women, Indigenous peoples and racialized minorities. Challenging anthropocentrism is therefore not simply an animal ethics problem, but part of a larger battle against exclusionary moral systems.

Biocentrism and Posthumanist Thought

Biocentrism has also shaped posthumanist philosophy -or the desire to decentre the human subject, and reconceptualize agency, ethics and responsibility as no longer limited to or bounded by humans. Posthumanist thinkers stress that anthropomorphism is a crucial element of an Enlightenment framework based on humanism, according to which humans are regarded as independent, rational and superior entities that are separate from nature (Braidotti, 2013).

In a posthumanist spirit, biocentrism shares an affinity with Relational Ethics in that it foregrounds human-animal-technological and eco systems interdependencies. Animals are not merely passive recipients of human activity but active creators of common worlds. This move destabilizes conventional animal ethics that are based on suffering alone, and re-values other ideas including living with, vulnerability and mutual becoming.

Within animal ethics, posthumanist biocentrism condemns even the best-informed welfare strategies as continuing to keep humans in control. For instance, to deal only through sterilization and relocation with stray animals while ignoring urban planning and also human responsibility still refers to an anthropocentric governance. From a biocentric–posthumanist perspective, it would entail structural transformations where animals can thrive in common worlds rather than just survive as managed by humans.

Implications for Food and Eating Ethics

Food ethics is one of the most conspicuous contexts in which anthropocentrism and biocentrism collide. Carnist constructions rationalize meat eating in terms of cultural custom, palate preference, or economic need. Even ethical farming systems don’t get around the basic assumption that we have the right to take animal lives for our own nutrition.

Biocentrism undermines this default assumption, by suggesting that the moral permissibility of killing animals for purposes other than satisfying desires is more dubious in those societies where non-animal food substitutes are available. Industrially produced animal products constitute a serious ethical failure from a biocentric perspective: here, sentient individuals are systemically violated -by the millions or billions- and ecosystems immeasurably degraded.

Furthermore, biocentrism connects animals ethics with environment protection. Livestock production is a leading culprit in deforestation, water depletion and greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, biocentric food ethics supports decreased animal consumption not just to prevent animal suffering but also to save ecosystems and the future generations. Ethical eating in this light becomes a multispecies moral practice rather than an individual lifestyle choice.

Education, Empathy, and Ethical Transformation

Ethical paradigms don’t live in isolation; they are bred through schooling and socializing. These anthropocentric values are inculcated from childhood through textbooks, media and cultural stories which present animals as resources, symbols or commodities. This sublimation of dominance desensitizes us to animal suffering.

Biocentrism for eth: Towards moral and ethical education based on empathic resonance, compassion and ecological literacy. Research in humane education shows that teaching children to recognize animal subjectivity leads to “cognitive extensions” of compassion toward human groups facing marginalization. Consequently, biocentrism has wider implications for welfare than just animal ethics: It helps to encourage a more compassionate society.

Universities and research organizations are also a key part of the picture. Bringing animal ethics, environmental humanities and human–animal studies to the classroom dislodges disciplinary silos and promotes a critical questioning of received moral frameworks on the part of students. This form of learning can support the shift from anthropocentric exploitation to bio-centred responsibility.

Towards an Integrative Ethical Framework

Although anthropocentrism and biocentriam are sometimes put in opposition to one another, there are philosophers who promote an integrated or pluralistic ethics incorporating concern for human well-being and for nonhuman life. In doing so it recognises legitimate human needs – like survival, cultural expression – but rejects the unnecessary harm and domination entailed in these activities.

Ideas such as compassionate conservation, ecological justice and multispecies ethics represent attempts to think outside the box of binary thinking. These approaches preserve human moral agency but de-center it in relation to a wider ecological responsibility. Biocentrism in this way is not a call for humanity to forsake its moral stakes, rather it insists on humility, and indeed self-restraint, and ultimately cohabitation.

Critiques of Anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism, which justifies both ecological degradation and animal suffering, has come under attack from many critics. This is also the problem that motivates environmentalists to critique anthropocentrism, e.g.; whether or not such arguments are successful depends upon our intuitions and values (Callicott, 1989).

To make matters worse, critics argue it is ethically incoherent: What if (as many of us believe) rationality or intelligence is the basis for moral standing? Then infants or the intellectually disabled would indeed have a lower status something that almost everyone finds hard to stomach. This reveals the dichotomy implicit in anthropocentrism, speciesism (Singer) as it is sometimes called.

Critiques of Biocentrism

Biocentrism Although biocentric claims have a certain moral ring to it, the arguments and practical implications are not always easily applicable. Detractors claim that if all living things are equally valuable, then no true ethical choices can be made. Agriculture, for instance, necessarily damages plants and small animals, leaving the question of moral paralysis.

Lastly, biocentrism may fail to appreciate human needs for culture, society, and survival. Moderate biocentrism or ecocentrism which combines respectful treatment of life while considering human interest (Rolston III 1988).

Relevance in Today’s Time At Both International and Indian Level

In an anthropocentric age, when Homo posed to act towards all other organisms in the world as a power among powers of extra-human physiological adaptation… that it become also thinkable for Mann to assimilate himself with respect to stake and clientele privileges even lesser empires. The changing climate, zoonotic diseases and habitat destruction speak to life and non-life being deeply interconnected.

In India articles like Art.51A(g), which prescribe the compassion toward all living being, indicate bio centric ethical under tone. Court decisions that affirm the sentience and dignity of animals also chip away at a long rooted anthropocentrism.

That social movements, veganism, animal activism and posthumanist scholarship marks a gradual ethical shift away from human-dominance to one of multispecies cohabitation.

Conclusion

The schism between anthropocentrism and biocentrism in animal ethics is a microcosm of the wider ethical battle regarding man’s role with nature. Although anthropocentrism has long been the primary mechanism of human domination and animal oppression, it now seems unable to provide sufficient justification to confront contemporary ethical and ecological challenges. For biocentrism, by honoring all forms of life in and of themselves, provides a more comprehensive and ethically compelling paradigm for rethinking human–animal interactions.

But the way out may not consist in an outright condemnation of anthropocentrism, but rather in its ethical rebirth. Incorporating biocentric ethics into our laws, public policies and day-today activities lays the foundation of a more caring, sustainable and ultimately peaceful relationship between humans and non-human animals. The transition from dominion to coexistence is finally not a step down but an advance of human dignity.

References

- Aristotle. (1998). Politics (C. D. C. Reeve, Trans.). Hackett Publishing.

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. Polity Press.

- Callicott, J. B. (1989). In Defense of the Land Ethic. SUNY Press.

- Descartes, R. (1984). Meditations on First Philosophy (J. Cottingham, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1641)

- Norton, B. G. (1991). Toward Unity among Environmentalists. Oxford University Press.

- Rolston III, H. (1988). Environmental Ethics: Duties to and Values in the Natural World. Temple University Press.

- Schweitzer, A. (1965). The Teaching of Reverence for Life. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation. HarperCollins.

- Singer, P. (2020). Animal Liberation Now. HarperCollins.

- Taylor, P. W. (1986). Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics. Princeton University Press.